This article was originally published by Tyler Durden at ZeroHedge.

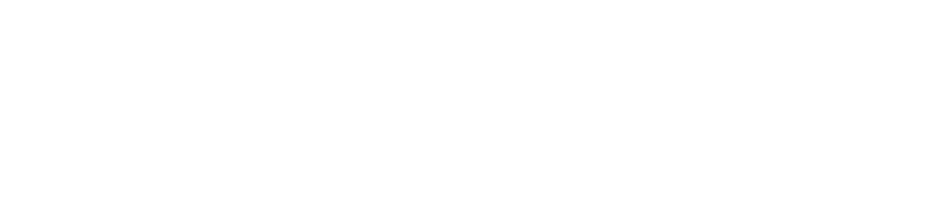

It may not be the off-the-charts gold buying observed in the second half of 2022, but central bank gold buying made a blistering start to 2023 when according to the latest report from the World Gold Council, demand for the hard currency by the world’s money-printing authorities reached 228 tonnes in Q1, a 176% increase compared to the 82.7 tonnes one year ago.

While lower than the figures seen in the previous two quarters this was nonetheless the strongest first quarter on record. According to the WGC, “This is all the more impressive considering it follows the record-breaking pace of demand last year.”

The rolling four-quarter total soared to a record 1,224 tonnes in Q1 following massive buying in recent quarters. As with the figures for both Q3 and Q4 2022, data for the current quarter contains a significant estimate for unreported activity.

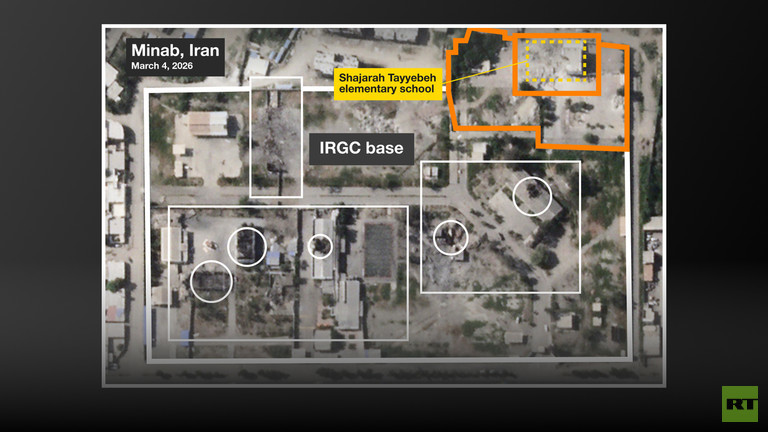

Four central banks accounted for the majority of reported purchasing during Q1:

- The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) was the largest single buyer during the quarter thanks to the addition of 69 tonnes of gold, the first increase in its gold reserves since June 2021, confirming that buying in Q1 was not only the domain of emerging market central banks. Gold reserves at MAS now total 222t, 45% higher than at the end of 2022.

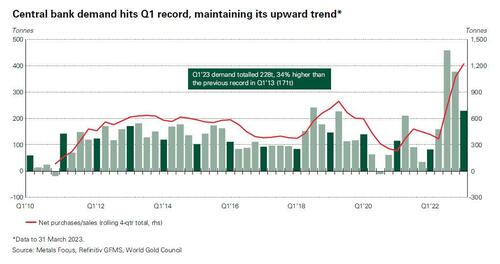

- The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) disclosed that its gold reserves had risen by 58t. Since recommencing reports of purchases in November 2022, the PBoC has added 120t to its gold reserves, lifting them to 2,068t (4% of total reported gold reserves). Overnight, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange reported the latest, April, reserves data which revealed that China’s gold reserves rose to a record 66.76 million ounces at the end of April, up from 66.5 million ounces at end-March.

- Turkey was again a big buyer of gold during the quarter: official reserves rose by 30t. Combined purchases of 45t in January and February were offset by a sale in March – the first since November 2021.11 15t of gold was sold into the local market following a temporary partial ban on gold bullion imports.12 Overall, this lifted total gold reserves to 572t (34% of total reserves).

- The Reserve Bank of India also added a modest 7t in Q1, lifting its gold reserves to 795t, while the Czech Republic (2t) and the Philippines (1t) were also notable buyers.

A significant update during Q1 came from the Central Bank of Russia in a resumption of its reporting of gold reserves, backfilling data from the end of January 2022 to date.

We can now see that in Q1 Russia’s official gold reserves fell by 6t, to 2,327t (25% of total reserves). However, even with this decline – possibly related to coin-minting – the country’s gold reserves are 28t higher than when it stopped reporting last year.

Selling was again much more modest by comparison. The Central Bank of Uzbekistan (-15t) and the National Bank of Kazakhstan (-20t) were the largest sellers of gold during the quarter. According to the WGC, it is not uncommon for central banks that purchase gold from domestic sources – as both Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan do – to be frequent sellers of gold. Cambodia (-10t), UAE (-1t) and Tajikistan (-1t) were the other notable sellers. Croatia reported a 2t reduction in its gold holdings in January but this was a transfer to the European Central Bank – which is required of all countries joining the euro area – and, as such, it does not represent a decline in the global universe of official sector gold.

Here is a chart summarizing the most notable central bank transactions during Q1.

The bottom line: expectations for strong central bank demand in 2023 have been borne out. Central bank buying remains robust, with little to indicate that this will change in the short term. As such, purchases will likely continue to outweigh sales for the foreseeable future and may explain in part why gold trades just shy of its all-time high north of $2,000 per ounce. But the exact pace of this net buying is difficult to determine.

0 Comments